August 6th, 1926. Cape Gris-Nez, France.

Twenty-year-old Trudy Ederle is standing at the shoreline, looking out at the grey, churning sea. It is early morning and the sky is impassive, reflecting none of its counterpart’s bad temper. Trudy is wearing a two-piece swimsuit she fashioned herself from a one-piece that was too loose and heavy, and dragged her back in the water. She is smeared, head to toe, in porpoise fat. The porpoise fat will reduce friction and keep her body insulated in the frigid waters as she makes her second attempt to swim across the English Channel unaided. The English Channel is twenty-one miles long and not, by any means, a smooth crossing.

By 1925, only five people had successfully swum the English Channel without artificial buoyancy - none of them women. In an era obsessed with extraordinary feats of the human spirit, the Channel was dangerously alluring to all serious athletes who wished to prove their strength and endurance in its querulous expanse. Most failed and many perished in attempting the crossing. Changing tides, currents, unforgiving tempests; jellyfish and sharks and shallows in which one can drown within sight of the Dover cliffs made it the ultimate challenge for the greatest swimmers of the time. Luckily, Trudy Ederle was indeed the greatest swimmer of her time.

Born in New York City in 1905 to German immigrant parents, Gertrude Ederle was never meant to survive. Contracting measles as a child, the illness was near-fatal. She did not succumb, but the illness left her with severe hearing loss that would affect her for the rest of her life. Despite her impairment and its implications for a young aspiring swimmer (for water would likely exacerbate her pre-existing hearing loss), Trudy’s father taught her to swim in the cool rapture of the Atlantic. When she was twelve years old, Trudy joined the Women’s Swim Association, and the world would never be the same.

It was under the wing of the WSA that Trudy Ederle became the fastest female swimmer in the world. Between 1921 and 1925, Trudy held a total of 29 national and world swimming records. She was a hero in her home country and yet, when she set her sights on the English Channel, the world chuckled derisively.

To prepare for her first attempt, Trudy trained with Jabez Wolffe, an experienced – but alas, unsuccessful – Channel swimmer, having attempted the crossing twenty-two times (yikes. Get another hobby). Jabez, like most men of the time, didn’t fancy himself a woman who could do it better. In fact, numerous sources say he deliberately hijacked Trudy’s attempt by pulling her from the sea prematurely under the pretence of safety concerns when in fact, Trudy was doing just fine and a mere six miles from the finish. Some sources even say he drugged her to slow her down. Needless to say, Trudy was pissed off and the two never trained together again.

A year later, she’s back at Cape Gris-Nez, watching the south-westerly wind whip the sea in front of her – the blue horizon that could easily kill her as cradle her, and the love of her life – into a frothing beast. Despite the rough conditions, she enters the water just after 7am. She maintains a steady, vigorous stroke, and within six hours makes it halfway to the English coast. As the day stretches onwards and the light begins to fail, crowds gather on the Dover shore to light fires and help Trudy find her way. At around 9:45pm, Trudy steps on to the beach near Kingsdown lifeboat station.

Accomplishing the crossing in just over 14 hours, Trudy broke the record by two hours. Her record would remain unbroken until 1950 (and was broken by another woman. Suck on it, Jabez Wolffe).

Trudy’s life story has all the makings of a legend. From overcoming a debilitating childhood illness to becoming America’s ‘Queen of the Waves’ and dismantling what society perceived to be the limits of the female body, Trudy Ederle changed the world. None of that would have happened without a bad bitch by the name of Charlotte Epstein.

In the early twentieth century, women swimming competitively was the butt of a joke at best and an offence to contemporary standards of modesty at worst. Women were, of course, the weaker sex. Physical exercise was considered dangerous for such delicate constitutions and anyway, they were supposed to be at home with the children. Society was cleanly delineated into female spaces and male spaces and to transgress such borders was to risk social ostracization. To hell with that, said Charlotte Epstein.

Founding the Women’s Swimming Association in 1917, Charlotte convinced the Amateur Athletic Union to allow female swimmers to register as athletes (in a time when ‘woman’ and ‘athlete’ in the same sentence was ludicrous). She also helped modernise the female swimsuit and championed women’s participation in the Olympics as well as the right to vote. Charlotte believed that women’s emancipation lay in the civic realm and the realm of sporting achievement; she fought tooth and nail for both. If it weren’t for women like Charlotte Epstein, who mentored Trudy Ederle and many other “swim girls” to greatness, we may well be confined, still, to archaic ideas of what women can achieve.

Historically, the right to swim has never been God-given but rather determined by who you are – your gender, your race, your class. Such inequalities persist today and are reflected across various the spectrum of physical activity. There’s problems across the board with equal participation and access to sporting greatness, but when it comes to swimming the implications of inequality are far greater. Swimming is not just a competitive sport – like gymnastics or horse-riding – nor is it merely a leisure activity to enjoy on the evenings and weekends. Swimming is a means of survival.

April 24th, 1960. Biloxi Beach, Mississippi.

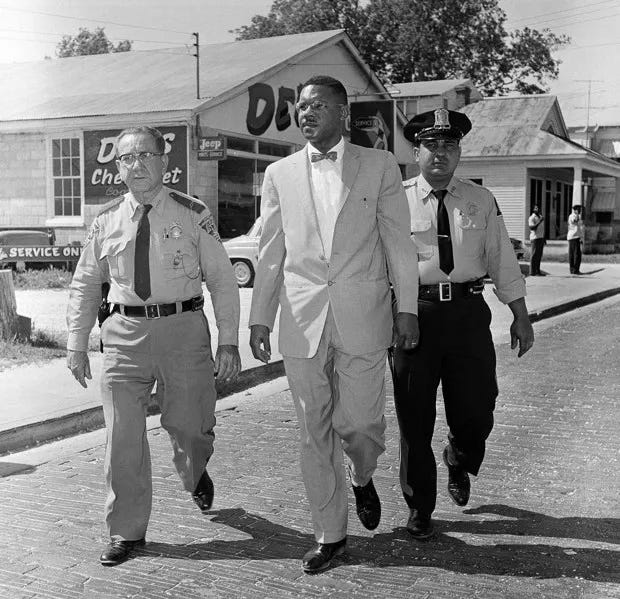

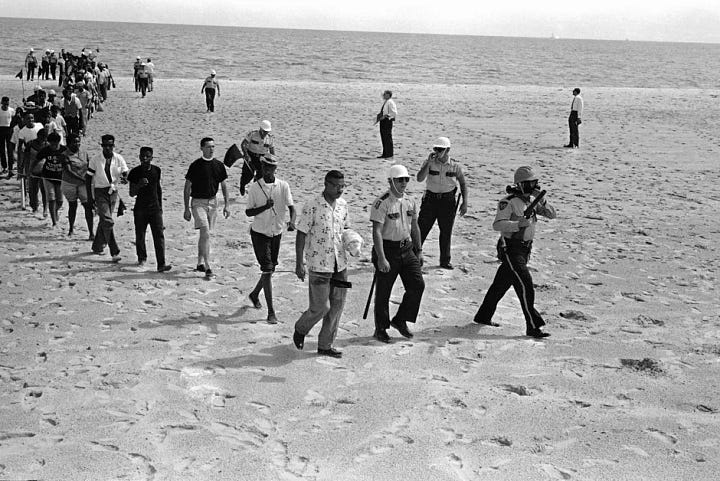

It is a balmy Sunday, and a crowd has gathered on the beach. Men in swimming trunks and women in loose-fitting dresses; teenagers kicking footballs; children running in and out of the sea under the watchful gaze of their parents who cool their feet in the shallows. There is a climbing heat in the air that cannot be attributed to the temperature. Friends call out to each other in an attempt to convey nonchalance, but no one can ignore the other crowd gathering just off the beach by the old Biloxi hotel. Even from this distance the intent of this crowd is apparent: their contempt rolls in like a tide. Dr. Gilbert Mason watches them carefully from the shore. He is the reason for the congregation around him. 125 black people – families, neighbours, church groups, storekeepers, physicians like himself – have gathered here on the hot sands of Biloxi because he asked them to. This congregation, in turn, is the reason for the mob of white men simmering on the edge of the beach. He can see that some of them are carrying weapons: chains, stones, lead pipes, pool sticks. Even more disquieting is the sight of officers from the local police force patrolling the edge of the angry murmur, at ease. It is obvious to anyone who has lived here in Biloxi for long enough, that the counter group is of the Sherrif’s own devising.

At any moment now – when the officers give the word - the mob will descend on them. All hell will break loose in what the New York Times will term, a few days from now, “the worse racial riot in Mississippi history”. The instigating event? Black people daring to swim on a whites-only beach.

In Jim Crow’s America, the frightening intimacy of public bathing was regulated to appease white fear and abhorrence of black bodies. In cities and towns, access to municipal pools was bound along racial lines, as were beaches in coastal areas. Pools for black people were usually crowded, unclean and underfunded; coastal allotments polluted and dangerous. The right to swim – and equally the right to leisure – was guaranteed only for those lucky enough to be on the white side of segregation. Therefore, when the Civil Rights movement started gaining momentum in the 1950s, pools and beaches quickly became symbolic interface zones in the fight for desegregation. Inspired by the countertop lunch ‘Sit-In’ protests, ‘Wade-Ins’ proliferated across the country, provoking white rage and ultimately violence in many instances.

The Biloxi Wade-In of 1960 was the second of three major protests led by Dr. Gilbert Mason. The first Wade-In happened inadvertently the year previous, when Gilbert and his friends went swimming at one of the beaches and were subsequently ordered to leave by a city policeman. Later that year, Gilbert and his supporters petitioned the Harrison County Board of Supervisors to allow equal access to all beaches in the area. It was later found that Mississippi state authorities had investigated the signers of the petition, looking into their jobs and credit histories in an effort to convince them to drop their case. As a result, some men who worked for white people lost their jobs and were forced to withdraw from the petition.

Gilbert was not deterred. When a statesman asked if a segregated portion of the beach would suffice, he said he would only be happy with access to “every damn inch of it.” Steadfast belief in his right to enjoy himself wherever his fellow white man could, steeled his resolve in the face of mounting opposition. Steadfast belief in his people’s right to revel in the sweet cool relief of the Gulf Sea on a hot spring day, as members of a public that did not ‘other’ anybody, brought him back to the beach in April 1960.

It bears him through the sight of his people running every which way as the vicious jaws of the mob closes in on them – the sight of his friends bowing in the surf beneath a wire cable someone’s son has fashioned into a whip, or wrestling beneath the knees of the man who owns the grocer they buy their food from – it bears him through the long night in the jail cell as the mob, dissatisfied with terrorising the beach protestors, turns the city upside down. Steadfast belief in the right to swim returns Gilbert Mason - and a growing body of supporters - to the beach in 1963 for a final Wade-In, adding to the clamour for the passing of the Civil Rights Act, which does so the next year.

Despite the Civil Rights Act officially desegregating public pools and beaches across the country, it would take another four years for Biloxi’s beaches to be declared open for all. Today, a plaque erected on the beach near the site of the 1960 Wade-In bears testimony to those who first dared to exercise their right to swim.

Swimming is freedom

Being able to swim, and enjoy it whenever we please, is something most of us – including myself – take for granted. I learned to swim as a child, and while I was no world-class swim champ, I felt at home in the water. My summers were spent in and out of the sea; I have fond memories of snorkelling in topaz Mediterranean waters, watching tiny vibrant fish flit by me. During the pandemic, escaping to the sea with friends and family quite literally kept me from losing my mind. I have forged sturdy friendships and fallen into dizzying romances in its salty embrace. I know the sea like an old, old friend. And I know that none of this would be true if I had never learned to swim.

Swimming is freedom. Swimming is a learned courage, a trust in the water and a trust in yourself. Trudy Ederle and Dr. Gilbert R Mason knew these truths well enough: their lives are testament to them. While living in two mostly incomparable contexts, both were possessing of a rare bravery that emboldened them to push back against the prejudices of their times. Both were dogged in their pursuit of the right to swim.

There are, of course, caveats to Trudy and Gilbert’s stories; caveats that help us understand why inequalities persist in swimming today. Trudy was a white woman who came from a comfortable background. In her early career, she was likely never in the same pool as a black woman. While the Wade-Ins Gilbert led were instrumental to the end of segregation in the US, the opening of pools and beaches to all races ultimately created a new kind of inequality: privileged whites retreated into back-garden pools and private beach clubs, effectively buying back segregation. Without financial or social backing, public pools shut down across the country, stripping communities of colour and working-class whites of their right to swim, and more importantly, to learn how to swim.

This troubling legacy manifests today in US drowning statistics: according to the CDC, black children between the ages of 10 and 14 are 3.6 times more likely to drown than their white counterparts. Disparities in swimming proficiency have also been noted between children of different socio-economic backgrounds: a 2020 study conducted with adolescents in Washington State found that 75% of students with mothers who had achieved more than an upper-secondary school degree participated in swimming lessons, compared to just 44% of students with mothers who had completed, at most, an upper-secondary degree.

As is the case for many race and class-based inequalities in sports participation, financial resources and proximity to adequate facilities are key determinants of whether a child learns to swim. Moreover, there is some evidence that socio-economically advantaged children are socialised to have a more positive view towards physical activity. Can it be argued, then, that introducing free swimming lessons into the school curriculum - such as in the UK, for example - balances the scales?

Not necessarily. In 2022, a Swim England survey of over 4000 participants from ethnically diverse backgrounds had some jarring results. 86% of white swimmers report themselves as competent swimmers (i.e. able to swim at least twenty-five meters unaided). Only 51% of swimmers from ethnically diverse (meaning in this instance Black, South Asian and East Asian) communities could say the same. Examining the gender dimensions of the data is even more alarming: 64% of females from Black, South Asian and East Asian communities can’t swim, in comparison to 17% of white females.

The breadth of such a gap tells me there is more at play here than economics. Cultural and religious practices – and a lack of sensitivity to these practices on the part of coaches and pool management – have created further barriers to learning to swim for minorities, particularly women. An absence of female-only swim classes and modest swimwear prohibits many Muslim women from learning to swim, for example.

Other minority identities may also be facing exclusion in the pool: while there is little research into transgender and non-binary individuals experiences relating to swimming, this study suggests that many genderqueer people may prefer to avoid swimming, owing to safety concerns and the ongoing media hysterics surrounding transgender athletes.

There are good stories, of course, like this one of Muslim girls learning to swim in burkinis in Zanzibar and the recent proliferation of queer swim clubs in the UK and Ireland. But we have a way to go before these kinds of stories – like Trudy’s and Gilbert’s – become the norm, and not the exception.

Discovering the right to swim for all is part of a larger movement towards equality of opportunity in every sphere of life, regardless of you or your child’s identity, background or race. Now, when I sink into the clean, heated water of my local pool, I am overcome with a sense of gratitude for what I have. Almost 100 years after Trudy Ederle rose from the waves at Dover, the very fact of me being able to swim is determined not by my intrinsic right as a human to be afforded every right to succeed, but rather the privilege that was my lucky draw upon entering this world.

In the pool, I pull my goggles down and adjust my cap: the lane ahead of me is still, the surface of the water yet unbroken. The right to swim, I think to myself as I submerge, should be understood as more than the physical act of swimming – of moving your arms and legs concurrently to travel through a body of water. If it were that simple, we might well have sorted the problem out by now. I start into an easy front crawl, turning my face every three strokes to breathe: yes. It’s more than that. The right to swim is the right to swim well, the right to swim safely, and the right to swim together.

Such an interesting and well composed read honey. As always - a delight